“Can I give you a polar bear tip?” asks Tee, a confident 13-year-old we meet on a visit to Churchill’s high school.

“When a bear is that close to you,” she says, measuring a distance of about a foot with her hands. “Make a fist and hit her in the nose.

“Polar bears have a very sensitive nose – they just run away.”

Tee didn’t need to put that advice to the test. But growing up here – next to the largest land predator on earth – means protecting bears is part of everyday life.

Victoria Gill/BBC

Victoria Gill/BBCSigns — in stores and cafes — remind anyone who goes outside to “watch out for bears.” My favorite is: “If a polar bear attacks, you have to do it.” defend yourself.”

Running from an attacking polar bear is, perhaps counterintuitively, dangerous. A bear’s instinct is to hunt prey, and polar bears can run at speeds of 25 miles per hour (40 km/h).

Important advice: Be alert and aware of your surroundings. Don’t walk alone at night.

Victoria Gill/BBC

Victoria Gill/BBCChurchill is considered the polar bear capital of the world. Every year, Hudson Bay – on the western edge of which the city lies – thaws, forcing the bears ashore. When frost sets in in the fall, hundreds of bears gather here and wait.

“We have freshwater rivers flowing into the area and cold water coming from the Arctic,” explains Alyssa McCall of Polar Bears International (PBI). “So this is where the freezing happens first.

“For polar bears, sea ice is a big dinner plate – it is access to their main prey, seals. They’re probably looking forward to a big meal of seal blubber – they haven’t eaten much on land all summer.”

Victoria Gill/BBC

Victoria Gill/BBCThere are 20 known subpopulations of polar bears throughout the Arctic. This is one of the southernmost and best studied.

“They are our fat, white, hairy canaries in the coal mine,” Alyssa explains. “We had about 1,200 polar bears here in the 1980s and have lost almost half of them.”

The decline depends on how long the bay is now ice-free, a period that will become longer as the climate warms. No sea ice means no frozen seal hunting platform.

“The bears here have been on land about a month longer than their grandparents,” explains Alyssa. “That puts pressure on mothers. (With less food) it’s harder to stay pregnant and feed the babies.”

Although their long-term survival is precarious, the bears attract conservation scientists and thousands of tourists to Churchill each year.

We join a PBI group searching for bears in the subarctic tundra – just a few miles from town. The team travels in a tundra buggy, a type of off-road bus with huge tires.

Kevin Church/BBC

Kevin Church/BBCAfter a few distant sightings, a breathtaking encounter occurs. A young bear approaches our slow two-buggy convoy and examines it. He sneaks up, sniffs one of the vehicles, then jumps up and puts two huge paws on the side of the buggy.

The bear casually falls back onto all fours, then looks up and briefly glances at me. It is deeply disorienting to look into the face of an animal that is at once adorable and potentially deadly.

“You could see him sniffing the vehicle and even licking it – using all his senses to investigate,” says PBI’s Geoff York, who has worked in the Arctic for more than three decades.

Kevin Church/BBC

Kevin Church/BBCBeing here during “bear season” means Geoff and his colleagues can test new technologies to detect bears and protect people. The PBI team is currently fine-tuning a radar system called Bear-Dar.

The test facility – a tall antenna with 360-degree scanning detectors – is installed on the roof of a lodge in the middle of the tundra near Churchill.

“It has artificial intelligence, so here we can basically teach it what a polar bear is,” explains Geoff. “It works around the clock and can also be seen at night and in poor visibility conditions.”

Kevin Church/BBC

Kevin Church/BBC Annie Edwards

Annie EdwardsProtecting the community is the job of the Polar Bear Alert Team – trained rangers who patrol Churchill daily.

We ride with ranger Ian Van Nest, who is looking for a stubborn bear that he and his colleagues were trying to drive away that day. “It turned around and came back (to) Churchill. He doesn’t seem interested in leaving.”

For bears that want to hang around the city, the team can use a live trap: a tubular container filled with seal meat for bait and with a door that the bear opens when it climbs inside.

“Then we took them to the storage facility,” Ian explains. The bears are held for 30 days. This period of time is intended to teach a bear that, although coming into the city to look for food is a negative thing, it does not endanger the animal’s health.

They are then moved – either on the back of a trailer or occasionally airborne by helicopter – and released further along the bay, away from people.

Victoria Gill/BBC

Victoria Gill/BBCCyril Fredlund, who works at Churchill’s new scientific observatory, remembers the last time a person was killed by a polar bear in Churchill in 1983.

“It was right in the city,” he says. “The man was homeless and staying in an abandoned building at night. There was a young bear there too – he knocked him down with his paw as if he were a seal.”

People came to help, Cyril recalls, but they could not get the bear away from the man. “It was like it was guarding its meal.”

Victoria Gill/BBC

Victoria Gill/BBCThe polar bear warning program was also launched at this time. Since then, no one has been killed by a polar bear here.

Cyril is now a technician at the new Churchill Marine Observatory (CMO). One of his tasks is to understand exactly how this environment will respond to climate change.

Underneath its retractable roof are two giant pools filled with water pumped in directly from Hudson Bay.

Victoria Gill/BBC

Victoria Gill/BBC“We can conduct all kinds of controlled experimental studies to study changes in the Arctic,” says Prof. Feiyue Wang.

One consequence of a less icy Hudson Bay is a longer operating season for the port, which is currently closed nine months of the year. A longer season as the bay thaws and becomes open water could lead to more ships coming and going from Churchill.

The aim of the studies at the observatory is to improve the accuracy of sea ice forecasts. The research will also examine the risks associated with port expansion. One of the first investigations is an experimental oil spill. Scientists plan to drain oil into one of the pools, test cleaning techniques and measure how quickly the oil breaks down in the cold water.

For Churchill Mayor Mike Spence, understanding how to plan for the future is vital to the city’s future in a warming world, particularly when it comes to moving goods in and out of Churchill.

“We are already thinking about extending the season,” he says, pointing to the port, which has closed operations for the winter. “In ten years there will be a lot of activity here.”

Victoria Gill/BBC

Victoria Gill/BBCClimate change poses a challenge to the polar bear capital of the world, but the mayor is optimistic. “We have a great city,” he says, “a wonderful community. And the summer season – (when people come to see the beluga whales in the bay) – is increasing.”

“Climate change poses challenges for all of us,” he adds. “Does this mean you cease to exist?” No – you adapt. You figure out how to benefit from it.”

While Mike Spence says “the future is bright for Churchill,” it might not be so bright for the Polar Bears.

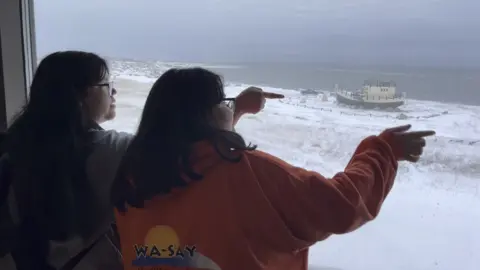

Tee and her friends look out at the bay from a window at the back of the school building. The Polar Bear Alert Team vehicles gather outside and attempt to drive a bear out of town.

“If climate change continues,” muses Tee’s classmate Charlie, “the polar bears might just stop coming here.”

The teacher approaches them to make sure that someone will pick up the children – so that they don’t go home alone. Everything is part of everyday life in the polar bear capital of the world.

Kate Stephens/BBC

Kate Stephens/BBC