Reuters

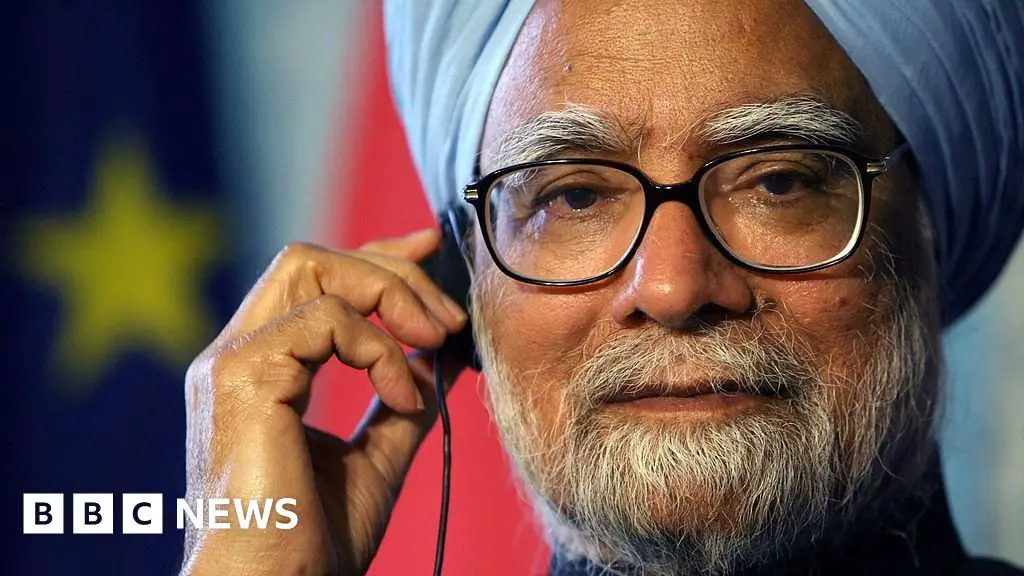

ReutersThe prospect of a timid politician is hard to imagine. Unless that politician is Manmohan Singh.

Since then Death of the former Indian Prime Minister on Thursday, Much has been said about the “kind and gentle politician” who changed the course of Indian history has influenced the lives of millions of people.

His state funeral will take place on Saturday and the Indian government has announced an official mourning period of seven days.

Despite an illustrious career – he was governor of India’s central bank and federal finance minister before becoming prime minister twice – Singh never seemed like much of a politician, lacking the public swagger of many of his colleagues.

Although he gave interviews and held press conferences, particularly during his first term as prime minister, he chose to remain silent even when his government was mired in scandal or his cabinet ministers faced allegations of corruption.

His gentlemanly manner was both lamented and revered.

Reuters

ReutersHis admirers said he was cautious not to start unnecessary battles or made big promises and that he focused on results – perhaps best exemplified by this Market-oriented reforms He inaugurated the post of Finance Minister, which opened India’s economy to the world.

“I don’t think anyone in India believes that Manmohan Singh can do anything wrong or corrupt,” he says former Congress party colleague Kapil Sibal once said,. “He was extremely cautious and always wanted to be on the right side of the law.”

His opponents, however, mocked him, saying he displayed a kind of vagueness unbecoming of a politician, let alone the prime minister of a country of more than a billion people. His voice – hoarse and breathless, almost like a tired whisper – often became the butt of jokes.

But that same voice also appealed to many who found him likeable in a world of politics where high and impulsive speeches were the norm.

Singh’s image as a media-shy, humble and introverted politician never left him, even as his contemporaries, including his own party members, went through dramatic cycles of reinvention.

But it was the dignity with which he handled every situation – even the difficult ones – that made him so memorable.

Born into a poor family in what is now Pakistan, Singh was India’s first Sikh prime minister. His personal story – a Cambridge and Oxford-educated economist who overcame insurmountable odds and rose through the ranks – coupled with his image of an honest and thoughtful leader had already made him a hero of the Indian middle class.

But in 2005, he surprised everyone when he publicly apologized in Parliament for the 1984 riots in which around 3,000 Sikhs were killed.

The riots, of which several members of the Congress party were accused, occurred after the assassination of then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi by her Sikh bodyguards. One of them later said they shot the Congress politician to avenge a military operation she had ordered against separatists hiding in Sikhism’s holiest temple in Amritsar, northern India.

It was a bold move – no other prime minister, including from the Congress party, had gone so far as to apologize. But it gave a healing effect to the Sikh community and politicians across party lines respected him for his courageous act.

Reuters

ReutersA few years later, in 2008, Singh’s low-key leadership style received more praise after he signed a landmark agreement with the US that ended India’s decades-long nuclear isolation and gave India access to nuclear technology and fuel for the first time since testing in 1974 .

The deal was heavily criticized by opposition leaders and Singh’s own allies, who feared it would jeopardize India’s foreign policy. However, Singh managed to save both his government and the agreement.

Global financial turmoil also occurred in 2008-2009, but Singh’s policies were credited with shielding India from it.

In 2009, he led his party to a landslide victory and returned for a second term as prime minister. In doing so, he cemented his image as a benevolent leader, or rather, the exciting idea of being a leader could be benevolent.

For many, he had become virtue personified, the “hesitant prime minister” who stayed away from the spotlight and refused any dramatic gestures, but also did not shy away from making bold decisions for the future of his country.

Then things started to unravel.

A series of corruption allegations – first in connection with the hosting of the Commonwealth Games, then in connection with the illegal allocation of coal fields – plagued the Congress party and Singh’s government. Some of these corruption allegations were later proven to be untrue or exaggerated. Some cases from this period are still pending in court.

But Singh had already started to feel some pressure. During his tenure, he made several attempts at reconciliation with India’s arch-rival Pakistan, hoping to thaw decades-old frosty relations.

The approach was sharply questioned in 2008 when a terror An attack led by a Pakistan-based terror group killed 171 people in the city of Mumbai.

The 60-hour siege, one of the bloodiest in the country’s history, opened a gulf of recriminations as the opposition blamed the tragedy on the government’s “soft stance” on terrorism.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn the years to come, other decisions Singh made completely backfired.

In 2011, an anti-corruption movement led by social activist Anna Hazare disrupted Singh’s government. The frail 72-year-old became a middle class icon as he called for tougher anti-corruption laws in the country.

As a middle-class hero himself, Singh was expected to be more sensitive to Hazare’s demands. Instead, the prime minister tried to suppress the movement by allowing police to arrest Hazare and break up his demonstration.

The move sparked a wave of public and media hostility against him. Those who once admired his reserved style wondered if they had misjudged the politician and began to view his quiet manner through a less generous lens.

The feeling intensified the next year when Singh refused to comment for more than a week on the horrific gang rape and murder of a young woman in Delhi.

To make matters worse, India’s economic growth slowed. Corruption grew and jobs shrank, triggering waves of public anger. And Singh’s humble personality, which once made his every move seem like a revelation, has been described by some as complacency, aloofness and even arrogance.

Yet Singh never tried to defend or explain himself and took the criticism calmly.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThat was until 2014. At a rare press conference, he announced he would not seek a third term.

But he also tried to clarify the matter. “I truly believe that history will judge me more kindly than the contemporary media or even the opposition parties in parliament,” he said after listing some of the greatest achievements of his term.

He was right.

As it turned out, neither the Congress nor Singh could fully recover from the damage as they lost the assembly elections to the BJP. But despite the many hurdles, Singh’s image as a friendly and demanding leader remained intact.

During his term as Prime Minister and despite a second term marked by controversy, he maintained an aura of personal dignity and integrity.

His policies appeared to be focused on the middle class and the poor – he approved and implemented multiple increases in the salaries of central employees, controlling inflation groundbreaking plans to education and career.

It may not have been enough to free him from the quandaries of politics or to save him from some of the failures of his career.

But there was more to his shyness; He was a leader with iron determination.