Reuters

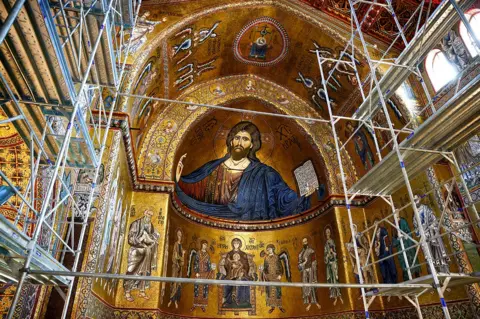

ReutersPerched on a hill overlooking the city of Palermo, Sicily, sits a lesser-known gem of Italian art: Monreale Cathedral.

Built in the 12th century under Norman rule, it features Italy’s largest Byzantine-style mosaics, the second largest in the world after those of Hagia Sophia in Istanbul.

Now this UNESCO World Heritage Site has undergone a major restoration to restore it to its former glory.

The Monreale mosaics were intended to impress, humble and inspire the visitor who passed through the central nave, in the tradition of Constantinople, the capital of the Roman Empire that remained to the east.

They cover 6,400 square meters and contain around 2.2 kg of solid gold.

Reuters

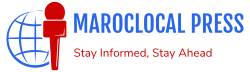

ReutersThe restoration took over a year, and during this time the cathedral became a kind of construction site, with a labyrinth of scaffolding erected on the altar and transept.

Local experts from the Italian Ministry of Culture led a series of interventions, starting with the removal of a thick layer of dust that had accumulated on the mosaics over the years.

They then repaired some of the tiles that had lost their enamel and gold leaf, making them look like black spots from below.

Finally, they intervened where the tiles were separating from the wall and fixed them.

Working on the mosaics was a challenge and a great responsibility, says Father Nicola Gaglio.

He has been a priest here for 17 years and has followed the restoration closely, not unlike a concerned father.

“The team approached this work almost on tiptoe,” he tells me.

“Sometimes there were some unforeseen problems and they had to pause operations while they found a solution.

“For example, when they got to the ceiling, they discovered that it had previously been covered with a yellowish layer of paint. They had to peel them off, literally like cling film.”

Zumtobel

ZumtobelThe mosaics were last partially restored in 1978, but this time the intervention was much more extensive and included the replacement of the old lighting system.

“There was a very old system. The light was dim, energy costs were high and it didn’t do justice to the beauty of the mosaics,” says Matteo Cundari.

He is country manager of Zumtobel, the company commissioned to install the new lights.

“The biggest challenge was to ensure that we highlighted the mosaics and created something that met the different needs of the cathedral,” he adds.

“We also wanted to create a fully reversible system that could be replaced in 10 or 15 years without damaging the building.”

Zumtobel

ZumtobelThis first part of the work cost 1.1 million euros. A second one is planned next, focusing on the central nave.

I ask Father Gaglio what it was like when the scaffolding finally came down and the mosaics shone in their new light. He laughs and shrugs his shoulders.

“When you see it, you’re overwhelmed with awe and can’t think about anything. It’s pure beauty,” he says.

“It is a responsibility to preserve such a world heritage. This world needs beauty because it reminds us of what is good in humanity and what it means to be male and female.”