Mosquitoes are usually associated with serious diseases such as malaria, dengue and yellow fever. However, researchers at Leiden University Medical Center (LUMC) and Radboud University in the Netherlands may have discovered a valuable new role for the insects: as vaccine distributors.

According to their scientists, they have managed to manipulate mosquitoes to deliver vaccines that could potentially provide significantly improved immunity against malaria.

The World Health Organization’s latest World Malaria Report found that an estimated 597,000 people died from malaria worldwide in 2023, with African countries bearing the brunt of the death toll – accounting for 95 percent of malaria deaths.

Scientists estimate that more than 240 million cases of malaria occur worldwide each year. Children and expectant mothers are most susceptible to the disease.

How does a mosquito-borne vaccine work?

The vaccine uses a weakened strain of Plasmodium falciparum (P falciparum), the parasite that causes the deadliest form of malaria in humans.

“We have removed an important gene from the malaria parasite, which means that the parasite can continue to infect people but does not make them sick,” explains vaccinator Meta Roestenberg, Professor of Vaccinology and Clinical Director of the Controlled Human Infection Center at LUMC.

Typically, the malaria parasite is transmitted to humans through a bite. The mosquito pierces the skin with its long, needle-like mouth (called a proboscis) and injects its saliva into the bloodstream before sucking blood. Parasites in saliva travel directly to the liver, where they multiply rapidly before leaving the liver to infect red blood cells with malaria. This leads to symptoms such as fever, chills and sweating.

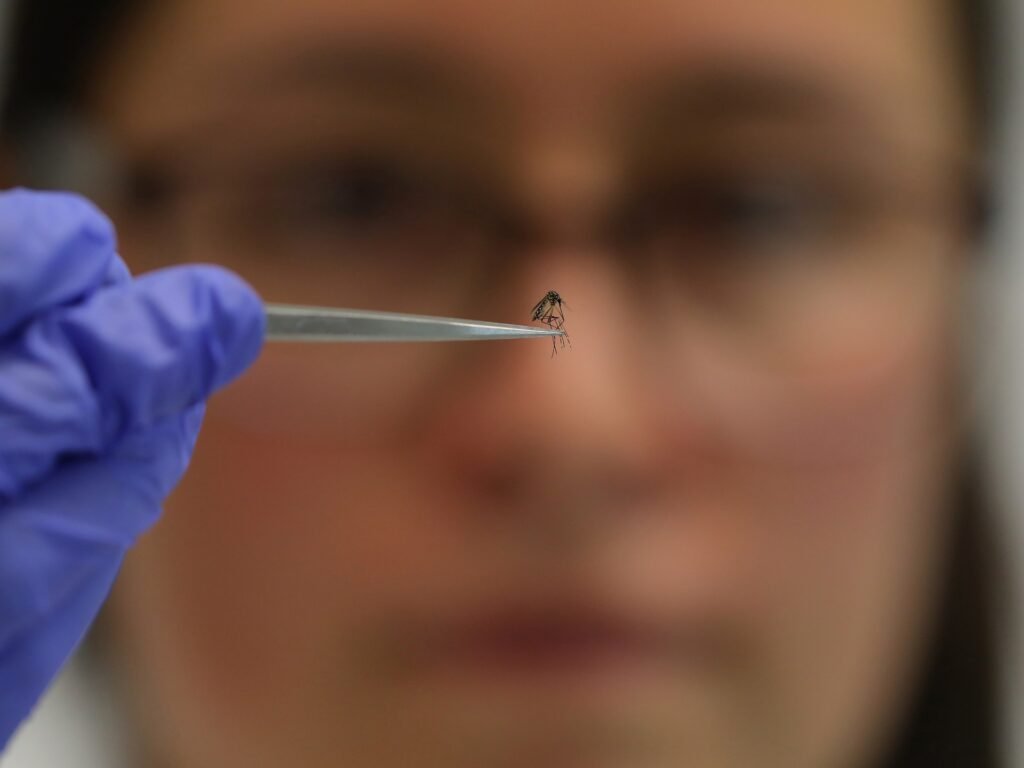

In the clinical trial, the research team used mosquitoes carrying the modified parasite to deliver the vaccine via bites, which is analogous to the natural transmission of malaria. The goal: to create a strong immune response in the liver and protect against malaria infection.

“Because the gene is switched off, this parasite cannot complete its development in the liver, cannot enter the bloodstream and therefore cannot cause symptoms of the disease,” said Roestenberg. “At least that was the theory.”

How were the experiments carried out?

The first study tested an injectable malaria vaccine derived from a genetically engineered parasite called PfSPZ GA1. The joint study with Sanara, a US biotechnology company developing vaccines, involved 67 participants from two cities in the Netherlands (Leiden and Nijmegen).

results of the study, published showed in May 2020 in Science Translational Medicine that the GA1 vaccine was safe to use and delayed the onset of malaria but did not protect participants from contracting the disease.

In the second trial, participants, none of whom had previously suffered from malaria, were given mosquito-borne versions of two vaccines – GA1 and a modified version of it, GA2. With the GA1 vaccine, the parasite multiplied in the liver within 24 hours. With the GA2 vaccine, the parasite multiplied over a longer period of time – up to a week – giving the immune system more time to recognize it and begin fighting it.

Researchers first tested doses of the GA2 vaccine on participants to determine its safety and tolerability. The participants were then divided into three groups: two groups tested the GA1 and GA2 vaccines, and one group received a placebo.

In each of the three sessions, participants received 50 mosquito bites: eight from mosquitoes infected with GA1, nine from mosquitoes infected with GA2, and three from uninfected mosquitoes. Participants who completed the vaccination phase then received five bites from mosquitoes carrying the malaria parasite.

What were the results?

The results of the study were published in November in the New England Journal of Medicine.

According to the study, 13 percent of the GA1-infected group and 89 percent of the GA2-infected group developed immunity to malaria. No one in the placebo group developed immunity.

Is further research needed?

Since the sample size of the clinical trial was small (20 participants), the GA2 vaccine still needs to be tested in larger trials, experts said.

Further research is also needed to determine how well the GA2 vaccine boosts the immune system over longer periods of time and whether it can protect against different strains of the malaria parasite in areas where the disease is common.

“Using the mosquito as a vector is an easier and faster way to transmit malaria sporozoites,” explained Roestenberg. “Of course, this is not sustainable in the long term and therefore the product must be developed as a vaccine in vials to be rolled out in Africa.”

“Mosquitoes could not be used to carry out vaccination on a large scale. This is only possible in the context of a clinical trial,” she added.

Have insects been used to administer vaccines before?

Japan, 2010

In 2010, Japanese scientists genetically modified mosquitoes to carry in their salivary glands a vaccine against leishmaniasis, a parasitic disease typically transmitted by sand flies. When a mosquito bites, the vaccine is released through saliva.

The study showed that rodents bitten by the “flying vaccines” developed antibodies to the parasite. However, researchers have yet to determine whether the resulting immune response is enough to prevent infection.

“After bites, protective immune responses are triggered, just like a traditional vaccination, but without pain and without cost,” lead researcher Shigeto Yoshida of Jichi Medical University said in a statement.

United States, 2022

In September 2022, a study of 26 participants in Seattle, Washington examined the potential of mosquitoes as vaccines.

In an experiment similar to the one in the Netherlands, mosquitoes served as vectors for malaria-causing Plasmodium parasites, which were genetically weakened using the gene-editing technology CRISPR. This was the first significant clinical trial to use mosquitoes as a direct vaccine delivery system with genetically engineered parasites.

Participants were first given the malaria vaccine and then the malaria virus to see if the vaccine protected them from contracting malaria.

The mosquito-administered vaccine was 50 percent effective, with seven of 14 participants contracting the disease.