BBC

BBCA Ukrainian official told the BBC he hoped a New Year’s prisoner exchange with Russia would happen “any day now,” although the arrangements could fall apart at the last minute.

Petro Yatsenko, from the Ukrainian Headquarters for the Treatment of Prisoners of War, said negotiations with Moscow over the prisoner exchange had become more difficult in recent months since Russian forces made significant progress at the front.

In 2024, there were only 10 exchanges, the lowest number since the all-out invasion began. Ukraine does not publish figures on prisoners of war held by Russia, but the total is estimated at over 8,000.

Russia has made significant progress on the battlefield this year, raising fears that the number of Ukrainians captured is rising.

One of those brought home in the last swap in September 2024 is Ukrainian Marine Andriy Turas. In an apartment in the Ukrainian city of Lviv, Andriy and his wife Lena tell me the remarkable story of their ordeal. Both were captured while defending the city of Mariupol in 2022.

“They lectured us about how Ukraine never existed,” Lena, a combat medic, said of her Russian captors. “They tried to erase our Ukrainian identity in our minds.”

Lena was released after two weeks in captivity. But the psychological scars of what she experienced in a Russian prisoner of war facility remain. “We kept hearing screams, we knew the men (in our unit) were being tortured,” she says.

“They beat us mercilessly, with fists, sticks, hammers and anything they could find,” says Andriy. “They stripped us naked in the cold and forced us to crawl on asphalt. Our legs were torn and we were scared and cold.”

“The food was terrible – sauerkraut and rotten fish heads. “It’s just a nightmare,” the Marine said. “It’s like waking up from a bad dream in the middle of the night, drenched in sweat and scared.”

Andriy’s imprisonment lasted much longer than his wife’s – two and a half years.

When he was released as part of the prisoner exchange three months ago, Andriy met his two-year-old son Leon for the first time. When the couple was captured by Russian forces, Lena didn’t know she was expecting it.

“When I found out I was pregnant, I just cried, first with joy, but then with sadness because I couldn’t tell my husband.”

“I constantly wrote him letters and told him that he would finally have the child he had wanted for so long,” says Lena, her eyes shining. “But he didn’t get a single letter.”

I ask Andriy how it felt to meet his son for the first time. “I thought I was the luckiest person in the world,” he says with a grin.

Although the BBC cannot independently verify everything Lena and Andriy told us, their reports are confirmed by international organizations that have interviewed hundreds of Ukrainian prisoners of war.

The U.N. says Russia subjects Ukrainian prisoners to “widespread and systematic torture and ill-treatment,” including severe beatings, electric shocks, sexual violence, suffocation, prolonged stressful positions, forced excessive exercise, sleep deprivation, mock executions, threats of violence and humiliation. “

In a statement to the BBC, the Russian Embassy in London said: “The allegations you have described are patently false. Captured Ukrainian militants will be treated humanely and in full accordance with the provisions of relevant Russian legislation and the Geneva Convention. They will be provided with good quality food, shelter, medical assistance, religious and intellectual nourishment.”

Andriy is being rehabilitated at a medical facility in Lviv. But he still has time to enjoy the holidays with his wife and son. It’s the Turas family’s first Christmas together and the best present for little Leon is having daddy at home.

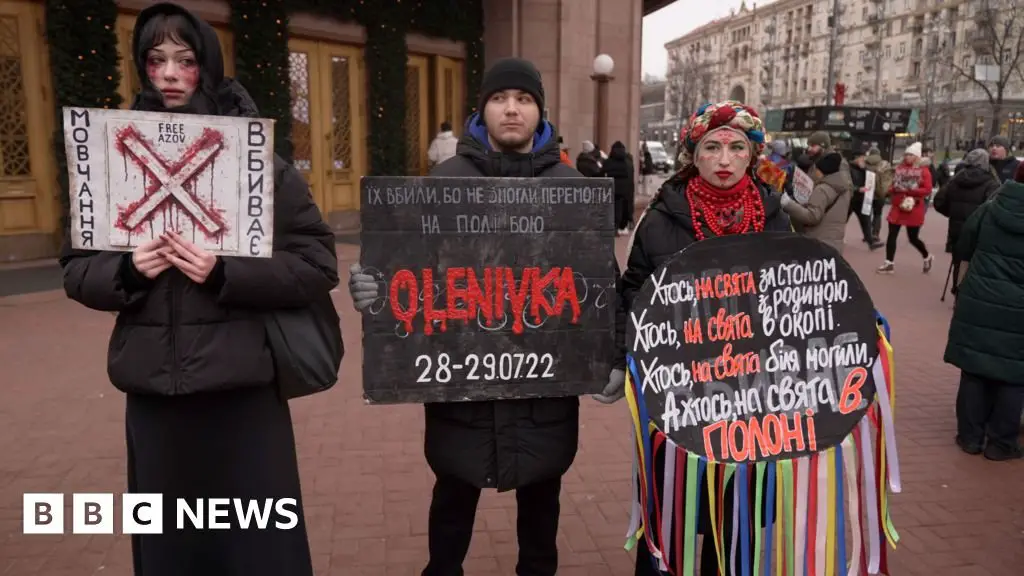

But many Ukrainians are still desperately waiting for news from their loved ones. Relatives and activists gather in central Kiev for a special Christmas demonstration to demand the release of Ukrainian prisoners.

They stand for hours in the biting cold on one of the capital’s main streets as passing motorists honk in a deafening cacophony of solidarity.

“We are hoping for a Christmas miracle,” said Tetiana, whose 24-year-old son Artem was captured almost three years ago. “The release of my son is my deepest wish. I have imagined our meeting 100 times, when he and I hug each other, and his eyes light up and he is finally in his homeland.

Also at the protest was 29-year-old Liliya Ivashchyk, a ballet dancer at the Kiev National Operetta Theater, holding a red poster. Her boyfriend Bohdan was captured by Russian forces in 2022. Since then she has had no contact with him.

“I could say it’s hard for me to be alone, but I don’t want to say that because I’m always thinking about how he’s doing over there,” Liliya says.

Backstage in the theater, Liliya shows us the messages that she still sends Bohdan almost every day – pictures of little hearts. “I miss him very much. He needs to be rescued and regain his freedom,” she says with a trembling lower lip. The messages are unread.

Liliya invites us to watch her perform in a special performance on Christmas Day. The dance is a festive favorite in Ukraine: Johann Strauss’ Danube Waltz, written in 1866 to lift the Austrian public’s spirits after a war. The theater is full.

“The Christmas holidays are a painful time,” she says as she prepares for the performance. “There’s not really a festive mood.”

At the end of the performance, theatergoers rush to collect their coats. After nearly three years of war, almost everyone here has a loved one fighting on the front lines, in captivity or killed in battle.

“Many people in Ukraine are faced with difficult situations,” says Liliya. “We’re just waiting until we can celebrate together again. We need to remember to thank our military for allowing us to have a holiday at all.”