NASA

NASAA NASA spacecraft has made history by making its closest ever approach to the sun.

Scientists received a signal from the Parker solar probe just before midnight Thursday after having no communication for several days during its scorching flyby.

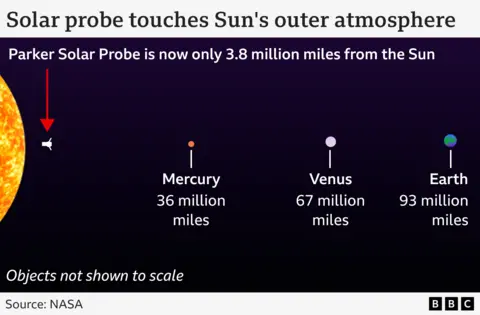

NASA said the probe was “safe” and functional after traveling just 3.8 million miles (6.1 million kilometers) from the sun’s surface.

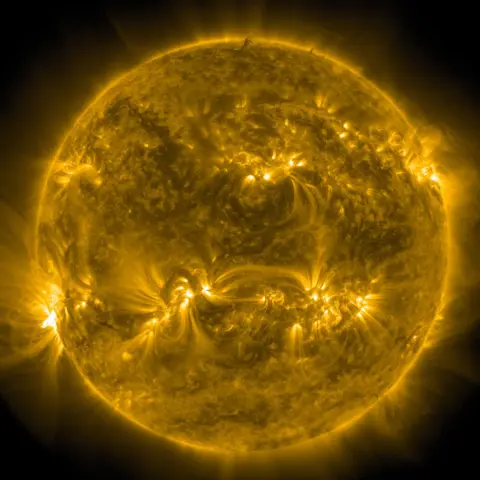

The probe plunged into our star’s outer atmosphere on Christmas Eve, enduring brutal temperatures and extreme radiation to improve our understanding of how the Sun works.

NASA then waited nervously for a signal, which had been expected at 05:00 GMT on December 28th.

According to the NASA website, the spacecraft moved at speeds of up to 430,000 miles per hour (692,000 km/h) and withstood temperatures of up to 1,800°F (980°C).

“This close-up study of the Sun allows Parker Solar Probe to make measurements that will help scientists better understand how material in this region is heated to millions of degrees and trace the origin of the solar wind (a continuous flow of material leaving the Sun). . “And discover how energetic particles are accelerated to near the speed of light,” the agency said.

Dr. Nicola Fox, NASA’s head of science, previously told BBC News: “People have been studying the sun for centuries, but you don’t experience the atmosphere of a place until you actually visit it.”

“And that’s why we can’t really experience our star’s atmosphere unless we fly through it.”

NASA

NASAThe Parker Solar Probe launched in 2018 and headed for the center of our solar system.

It had already flown past the sun 21 times and was getting closer and closer, but the visit on Christmas Eve was record-breaking.

At its closest approach, the probe was 3.8 million miles (6.1 million km) from our star’s surface.

This may not sound so close, but Dr. Fox put it into perspective. “We are 93 million miles from the sun. So if I put the sun and the earth one meter apart, the Parker Solar Probe is 4cm away from the sun – so that’s close.”

The probe was exposed to temperatures of 1,400 °C and radiation that could have damaged the onboard electronics.

It was protected by an 11.5 cm (4.5 in) thick carbon composite shield, but the spacecraft’s tactic was to enter and exit quickly.

In fact, it moved faster than any man-made object, traveling at 430,000 miles per hour – the equivalent of flying from London to New York in under 30 seconds.

Parker’s speed was due to the enormous gravitational pull he felt as he fell toward the sun.

PA Media

PA MediaSo why go to all this effort to “touch” the sun?

Scientists hope that as the spacecraft passed through our star’s outer atmosphere – its corona – it collected data that will solve a long-standing mystery.

“The corona is really, really hot, and we have no idea why,” explained Dr. Jenifer Millard, astronomer at Fifth Star Labs in Wales.

“The surface of the sun is about 6,000°C or so, but the corona, that thin outer atmosphere that you can see during eclipses, reaches millions of degrees – and that’s further away from the sun. So how does this atmosphere get hotter?”

The mission will also help scientists better understand the solar wind – the constant stream of charged particles erupting from the corona.

When these particles interact with the Earth’s magnetic field, the sky lights up with dazzling auroras.

But this so-called space weather can also cause problems, crippling power grids, electronics and communications systems.

“Understanding the sun, its activity, space weather and the solar wind is so important to our daily life on Earth,” said Dr. Millard.

NASA

NASANASA scientists had to wait anxiously over Christmas while the spacecraft was out of contact with Earth.

Dr. Fox had expected that as soon as a signal was sent home, the team would send her a green heart to let her know the probe was OK.

She previously admitted she was nervous about the bold attempt but had confidence in the investigation.

“I’ll worry about the spaceship. But we really designed it to withstand all of these brutal, brutal conditions. It’s a tough, tough little spaceship.”