China has quietly mobilized thousands of fishing boats in recent weeks to form giant floating barriers at least 200 miles long, demonstrating a new level of coordination that could give Beijing more ability to assert control in contested seas.

The two most recent operations went largely unnoticed. A New York Times analysis of ship tracking data reveals for the first time the scale and complexity of the maneuvers.

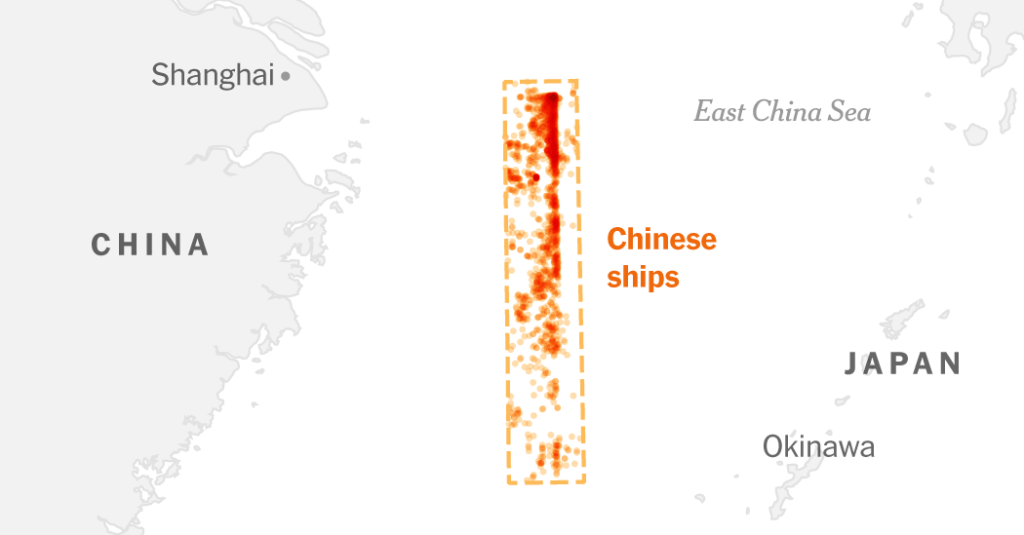

Last week, about 1,400 Chinese vessels abruptly stopped their usual fishing activities or left their home ports and gathered in the East China Sea. By January 11, they had coalesced into a rectangle that stretched more than 200 miles. The formation was so tight that some approaching cargo ships appeared to have to avoid it or zigzag through it, ship tracking data showed.

Ship formation on January 11th

Maritime and military experts said the maneuvers suggested China was strengthening its maritime militia, which consists of civilian fishing boats trained to take part in military operations. They said the maneuvers showed Beijing could quickly bring together large numbers of boats in disputed seas.

The Jan. 11 exercise followed a similar operation last month when about 2,000 Chinese fishing boats gathered in two long, parallel formations in the East China Sea on Christmas Day. Each spanned 290 miles, about the distance from New York City to Buffalo, and formed an inverted L-shape, ship position data shows. The two meetings, which took place weeks apart in the same waters, suggested coordinated action, analysts said.

Ship formation on December 25th

The unusual formations were discovered by Jason Wang, chief operating officer of ingeniSPACEa data analysis company and were independently verified by The Times using ship location data provided by Starboard Maritime Intelligence.

“I thought to myself, ‘This isn’t right,'” he said, describing his reaction when he spotted the fishing boats on Christmas Day. “I mean, I’ve seen a few hundred – let’s say several hundred,” he said, referring to Chinese boats he had previously tracked, “but nothing of this size or in this distinctive formation.”

In a conflict or crisis, such as over Taiwan, China could mobilize tens of thousands of civilian vessels, including fishing boats, to clog sea lanes and complicate military and supply operations by its opponents.

Chinese fishing boats would be too small to effectively enforce a blockade. But they could potentially impede the movement of American warships, said Lonnie Henley, a former U.S. intelligence officer who has done so studied China’s maritime militia.

The masses of smaller boats could also act “as missile and torpedo decoys, overwhelming radars or drone sensors with too many targets,” said Thomas Shugart, a former U.S. naval officer who now works in the U.S. Navy Center for a New American Security.

Analysts tracking the ships were impressed by the scale of the maneuvers, even given China’s scale Civilian Boat Mobilization Recordsin which, for example, boats were anchored on disputed reefs for weeks in order to enforce Beijing’s claims in territorial disputes.

“The sight of so many ships operating together is breathtaking,” said Mark Douglas, an analyst at Starboarda company with offices in New Zealand and the United States. Mr. Douglas said he and his colleagues had “never seen a formation of this size and discipline before.”

“The level of coordination to get so many ships into a formation like this is significant,” he said.

The assembled boats held relatively stable positions and did not sail in patterns typical of fishing, such as looping or back-and-forth paths, analysts said. The ship location data is based on the navigation signals broadcast by the ships.

The operations appeared to mark a bold step in China’s efforts to train fishing boats to assemble en masse to impede or monitor other countries’ vessels or to help Beijing assert its territorial claims by establishing a perimeter, Mr. Wang said ingeniSPACE.

“They are increasing in size, and that increase in size shows that they are able to better command and control civilian ships,” he said.

The Chinese government has not publicly commented on the fishing boats’ activities. The ship signal data appeared to be reliable and not “spoofed” – that is, manipulated to give false impressions about the boats’ positions – both Mr. Wang and Mr. Douglas said.

When researchers at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington were contacted by the Times with these findings, they confirmed that they had observed the same groups of ships using their own ship location analysis.

“They’re almost certainly not fishing, and I can’t think of any explanation that doesn’t rely on government direction.” Gregory Polingwrote the director of the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative at CSIS in emailed comments.

The fishing boats gathered in the East China Sea, near major shipping routes that branch off from Shanghai, one of the world’s busiest ports. Cargo ships ply the sea every day, including those carrying Chinese exports to the United States.

These are maritime arteries that China would seek to control in a clash with the United States or its Asian allies, including in a possible crisis over Taiwan, the island democracy that Beijing claims as its territory.

“My best guess is that this was an exercise to see how civilians would behave if asked to assemble on a large scale in a future emergency, perhaps in support of quarantine, blockade or other pressure tactics against Taiwan,” Mr. Poling wrote. “Quarantine” is a naval operation to seal off an area to avoid an act of war.

The January boat maneuvers took place shortly afterwards Beijing held military exercises for two days around Taiwan, including conducting naval maneuvers to blockade the island. Beijing is also embroiled in a bitter dispute with Japan over its support for Taiwan.

The fishing boat operations could have been carried out to signal “opposition to Japan” or to practice possible confrontations with Japan or Taiwan, he said Andrew S. Ericksona professor at the US Naval War College who studies China’s maritime activities. He noted that he was speaking for himself, not his college or the Navy.

Both Japan’s defense ministry and coast guard declined to comment on the Chinese fishing boats, citing the need to protect their intelligence-gathering capabilities.

Some of the fishing boats had participated in previous maritime militia activities or belonged to fishing fleets known to have been involved in militia activities, according to a review of Chinese state media reports. China does not publish the names of most of its maritime militia vessels, making it difficult to determine the status of the boats involved.

But the boats’ close coordination showed it was likely “an at-sea mobilization and exercise of maritime militia forces,” Professor Erickson said.

China has deployed dozens or even hundreds of maritime militia fishing boats to support its navy in recent years, sometimes by swarming, dangerous maneuvering and physically jostling other boats in disputes with other countries.

The recent mass gathering of boats appeared to show that maritime militia units are better organized and better equipped with navigation and communications technology.

“It represents an improvement in their ability to deploy and control large numbers of militia ships,” said Mr. Henley, the former U.S. intelligence officer who is now a nonresident senior fellow at the organization Institute for Foreign Policy Research in Philadelphia. “This is one of the biggest challenges in making maritime militia a useful tool for combat support or sovereignty protection.”

Choe Sang-Hun contributed reporting from Seoul and Javier C. Hernández and Kiuko Notoya contributed reporting from Tokyo.

Data source: Starboard Maritime Intelligence.

About the data: We analyzed automatic identification system (AIS) data from vessels transmitting positions near the formation during the 24-hour periods of December 25, 2025 and January 11, 2026, and either follow the Chinese fishing vessel naming convention or are registered as Chinese-flagged fishing vessels. Vessels do not always transmit information and may transmit incorrect information. The positions shown on the maps are the last known positions at the respective time.