Switch off the editor’s digest free of charge

Roula Khalaf, editor of the FT, selects her favorite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In 1947 the first transistor, the basic building block for a digital computer, was produced with a semiconductive material that was considered ideal for the task: Germanium. The idea of using silicon only came in the middle of the next decade, and it was not until 1960 that a thin layer of oxidized silicon, which can be found in today’s most frequently used transistors, was added.

Quantum computing, the great hope of solving problems that today’s computers are out of reach, is still struggling to achieve its own silica gum. Some of the largest technology companies have started to build their attempts to build a work machine, that the field finally exceeded the threshold between interesting scientific experiment and practical technical challenge.

However, there is no consensus about how best to make the most basic elements of quantum computers that are referred to as qubits – or whether future machines are more based on a number of different technologies than just one, with different types of machines suitable for different computer problems.

This lack of agreement on something so fundamental is a sobering memory of how far Quantum Computing still has to prove to prove itself. It also indicates that the race between some of the largest technology companies will probably produce winners and losers because some quBITs do not go out.

This week it was the turn of Amazon, a relative newcomer to the quantum hardware area, to complement the multiplication of technologies. His entry, known as Cat quibitsIs named after Schrödinger’s cat, one of the most misunderstood experiments of thought in science (the Austrian physicist used his cat -like paradox to point out that it was nonsensical to believe that a cat that was closed in a box in a box could have to do at the same time).

Cat qubits follow their origins for research at Yale University a decade ago and were first led by the French start-up Alice & Bob, whose donation campaigns are a sign of growing trust in the past month that technology is ready to go beyond the laboratory. The components are designed in such a way that one of the common fault types that affect all qubits and they are less susceptible to the “noise” that builds up in machines when the systems are taken to scales.

All quantum computers work by encoding information about several qubits to compensate for the instability of each individual component. The less error -prone to the quBITs, the less the number needs. The first rudimentary quantum chip of Amazon, which was made from nine quBITs, achieves the performance of other quantum chip species using 50-100, says Oskar Painter, the company’s quantum hardware.

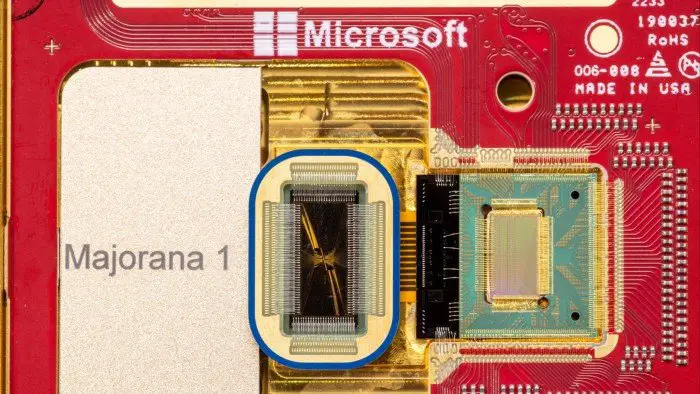

The company’s progress, characterized by a paper in Naturefollows Microsoft’s assertion That it finally has something from its 20-year striving for an even more radical qubit type based on the exploitation of a new state of matter.

The prototype chips of the two companies – Microsoft Majorana 1 and Amazon’s Ocelot – are still behind the managers in front of the area, such as Google’s Willow and IBM’s Heron. These and others are based on different types of qubit with a longer track record. Even if Microsoft and Amazon are right to have superior components, they have a long way to show them that they can be used to build practical machines that skip competition.

There are obvious parallels to the current race between the largest technology companies to develop their own AI chips. According to Painter, Amazon’s goal in Quantum is the same as in the AI: While his cloud arm, AWS, plans to offer customers any kind of chip on the market, his own internal chip will act as an anchor. This makes the chip efforts of strategic importance for the largest technology companies in both AI and quantum.

In Quantum, a lot depends on whether the race turns out to be a sprint or marathon. Recent progress such as progress in error correction Google reported In the past year, optimistic estimates of a practical quantum computer brought up optimistic estimates by the end of the decade. The CEO of Nvidia, Jensen Huang, shaken the quantum world with its estimate of 15 to 30 years at the beginning of this year, while the painter predicts at Amazon that work machines are still 10-20 years away.

If cautious estimates are correct, it is questionable how many of today’s quantum research efforts will survive. A decade would punish a decade for the best-financed start-ups. And since the various quantum architectures are reduced, a certain consolidation of less fundamental technologies seems likely.